Congenital Heart Disease

Overview

An atrial septal defect (ASD) is a hole in the heart wall between the two upper chambers. The condition is present at birth. Small defects may never cause a difficulty and may be found incidentally. It is also possible that small atrial septal defects may close on their own during infancy or early childhood.

Large and long-standing atrial septal defects can damage the heart and lungs. An adult who has had an undetected atrial septal defect for decades may have a shortened lifespan from heart failure or high blood pressure that affects the arteries in the lungs (pulmonary hypertension). Surgery may be necessary to repair atrial septal defects to prevent complications.

Symptoms

Many babies born with atrial septal defects do not have associated signs or symptoms. In adults, signs or symptoms may begin around the age of 30, but in some cases, signs and symptoms may not occur until decades later.

Atrial septal defect signs and symptoms may include:

- Shortness of breath, especially when exercising.

- Fatigue

- Swelling of legs, feet or abdomen.

- Heart palpitations (increased heart beats that can be felt by the patient) or skipped beats.

- A stroke

- Heart murmur(a whooshing sound that can be heard through a stethoscope).

- Causes

Why do heart defects develop?

Doctors know that heart defects present at birth arise from errors early in the foetal heart’s development, but there is often no clear cause. Genetics and environmental factors may play a role.

How does the heart work with an atrial septal defect?

An atrial septal defect allows freshly oxygenated blood to flow from the left upper chamber of the heart into the right upper chamber of the heart. There, it mixes with deoxygenated blood and is pumped to the lungs, even though it is already refreshed with oxygen.

If the atrial septal defect is large, this extra blood volume can overfill the lungs and overwork the right side of the heart. If not treated, the right side of the heart eventually enlarges and weakens. If this process continues, blood pressure in the lungs may increase as well, leading to pulmonary hypertension.

Atrial septal defects can be of several types, including:

- Secundum: This is the most common type of ASD and occurs in the middle of the wall between the atria.

- Primum: This defect occurs in the lower part of the atrial septum and may occur with other congenital heart problems.

- Sinus venosus: This rare defect usually occurs in the upper part of the atrial septum.

- Coronary sinus: In this rare defect, a part of the wall between the coronary sinus — which is part of the vein system of the heart — and the left atrium is missing.

Risk factors

It is not known why atrial septal defects occur but congenital heart defects appear to run in families and sometimes occur with other genetic problems such as Down’s syndrome.

Some conditions that an individual has or that occur during pregnancy may increase the risk of having a baby with a heart defect, including:

- Rubella infection: Becoming infected with Rubella (German measles) during the first few months of pregnancy can increase the risk of foetal heart defects.

- Use of certain medications, tobacco, alcohol or drugs such as cocaine during pregnancy can harm the developing foetus.

- Diabetes or lupus: If the mother of the newborn baby has diabetes or lupus she may be more likely to have a baby with a heart defect.

- Obesity: Mother being extremely overweight may play a role in increasing the risk of having a baby with a birth defect.

- Phenylketonuria (PKU): If the mother has PKU and is not following a PKU meal plan, she is more likely to have a baby with a heart defect.

Complications

A small atrial septal defect may never cause any problems. Small atrial septal defects often close during infancy.

Larger defects can cause serious problems, including:

- Right-sided heart failure.Heart rhythm abnormalities (arrhythmias).

- Increased risk of a stroke.

- Shortened lifespan.

Less common serious complications may include:

- Pulmonary hypertension: If a large atrial septal defect goes untreated, increased blood flow to the lungs increases the blood pressure in the lung arteries.

- Eisenmenger syndrome: Pulmonary hypertension can cause permanent lung damage. This complication usually called Eisenmenger syndrome normally develops over many years and occurs uncommonly in people with large atrial septal defects.

Atrial septal defect and pregnancy

Most women with an atrial septal defect can tolerate pregnancy without any problems. However having a larger defect or having complications such as heart failure, arrhythmias or pulmonary hypertension can increase the risk of complications during pregnancy. Doctors strongly advise women with Eisenmenger syndrome not to become pregnant because it may be dangerous to their lives.

The risk of congenital heart disease is higher for children of parents with congenital heart disease whether it is present in the father or the mother. Anyone with a congenital heart defect,(repaired or not), who is considering starting a family should carefully discuss it beforehand with a doctor. Some medications may need to be stopped or adjusted before a woman plans to conceive because they can cause serious problems for a developing foetus.

Prevention

In most cases, atrial septal defects cannot be prevented. If a woman is planning to conceive, she needs to schedule a preconception visit with a doctor. This visit should include:

- Getting tested for immunity to Rubella: If a woman is not immune, consult the doctor about getting vaccinated.

- Going over one’s current health conditions and medications: An individual needs to carefully monitor certain health problems during pregnancy. The doctor may also recommend adjusting or stopping certain medications before one gets pregnant.

- Reviewing family medical history: If one has a family history of heart defects or other genetic disorders, she must consider talking with a genetic counsellor to determine what the risk might be before getting pregnant.

Diagnosis

A doctor may first suspect an atrial septal defect or other heart defects during a regular check-up if he or she hears a heart murmur while using a stethoscope.

If the doctor suspects the child has a heart defect he may request one or more of the following tests:

- Echocardiogram: This is the most commonly used test to diagnose an atrial septal defect. During an echocardiogram, sound waves are used to produce a video image of the heart. It allows the doctor to see the heart’s chambers and measure their pumping strength.This test checks heart valves and looks for any signs of heart defects. Doctors may use this test to evaluate the condition and determine the treatment plan. Some atrial septal defects can be found during an echocardiogram done for another reason.

- Chest X-ray: An X-ray image helps the doctor to see the condition of the heart and lungs. An X-ray may identify conditions other than a heart defect that may explain signs or symptoms.

- Electrocardiogram (ECG): This test records the electrical activity of the heart and helps identify heart rhythm problems.

- Cardiac catheterisation: In this test, a thin flexible tube is inserted into a blood vessel at the groin or arm and guided towards the heart. Through catheterisation, doctors can diagnose congenital heart defects and also test how well the heart is pumping and check the function of the heart valves. Using catheterisation, the blood pressure in the lungs can also be measured.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): A MRI is a technique that uses a magnetic field and radio waves to create 3-D images of the heart and other organs and tissues within the body. A doctor may request an MRI if echocardiography cannot definitively diagnose an atrial septal defect.

- Computerised tomography (CT) scan: A CT scan uses a series of X-rays to create detailed images of the heart. A CT scan may be used to diagnose an atrial septal defect if echocardiography has not diagnosed an atrial septal defect.

Treatment

Many atrial septal defects close on their own during childhood. From those that don’t close, the small atrial septal defects do not cause any problems and may not require any treatment. But many persistent atrial septal defects eventually require surgery to be corrected.

Surgery

Many doctors recommend repairing an atrial septal defect diagnosed during childhood to prevent complications as an adult. Doctors may recommend surgery to repair medium-to large-sized atrial septal defects. However, surgery is not recommended if one has severe pulmonary hypertension because it might make the condition worse.

For adults and children, surgery involves sewing close or patching the abnormal opening between the atria. Doctors will evaluate the condition and determine which procedure is most appropriate. Atrial septal defects can be repaired using two methods:

- Cardiac catheterisation: In this procedure, doctors insert a thin tube into a blood vessel in the groin and guide it to the heart using imaging techniques. Through the catheter, doctors insert a mesh patch or plug into place to close the hole. The heart tissue grows around the mesh, permanently sealing the hole.

- Open-heart surgery: This type of surgery is done under general anaesthesia and requires the use of a heart-lung machine. Through an incision in the chest, a surgeon uses patches to close the hole. This procedure is the preferred treatment for certain types of atrial septal defects (primum, sinus venosus and coronary sinus) and these types of atrial defects can only be repaired through open-heart surgery. This procedure may also be conducted using small incisions for some types of atrial septal defects.

Follow-Up Care

Follow-up care depends on the type of defect and whether other defects are present. Repeated echocardiograms are done after hospital discharge, one year later and then as recommended by the patient or the cardiologist / cardiothoracic surgeon. For simple atrial septal defects closed during childhood, only occasional follow-up care is generally needed.

Adults who have had atrial septal defect repair need to be monitored throughout life to check for complications, such as

- Pulmonary hypertension

- Arrhythmias

- Heart failure or valve problems.

- Follow-up exams are typically done on a yearly basis.

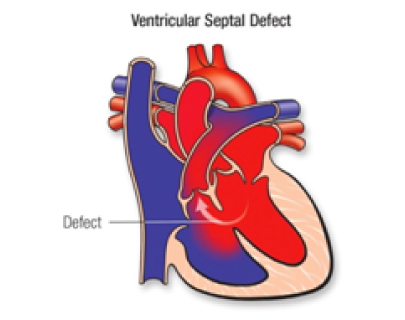

Overview

A ventricular septal defect (VSD) is a hole between the right and left pumping chambers of the heart. The heart has four chambers: a right and left upper chamber called an atrium and a right and left lower chamber called a ventricle. The hole occurs in the wall that separates the heart’s lower chambers (ventricles) and allows blood to pass from the left to the right side of the heart. A small ventricular septal defect may cause no problems, and many small VSDs close on their own. Medium or larger VSDs may need surgical repair early in life to prevent complications. Ventricular septal defects are among the most common congenital heart defects, occurring in 0.1 to 0.4 percent of all live births and making up about 20 to 30 percent of congenital heart lesions

Symptoms

Signs and symptoms of serious heart defects often appear during the first few days, weeks or months of a child’s life. Ventricular septal defect symptoms in a baby may include:

- Poor weight gain

- Fast breathing or breathlessness.

- Fatigue, increased sweating

- Shortness of breath or a heart murmur heard when listening to the heart with a stethoscope.

A doctor may not notice signs of a ventricular septal defect at birth. If the defect is small, symptoms may not appear until later in childhood — if at all. Signs and symptoms vary depending on the size of the hole and other associated heart defects.

A doctor may first suspect a heart defect during a regular check-up if he or she hears a murmur while listening to the baby’s heart sound with a stethoscope. Sometimes VSDs can be detected by an ultrasound before the baby is born.

Sometimes a VSD is not detected until a person reaches adulthood.

Causes

There is no clear cause of occurence of ventricular septal defect. Genetics and environmental factors may play a role. VSDs can occur alone or with other congenital heart defects. During foetal development, a ventricular septal defect occurs when the muscular wall separating the heart into left and right sides fails to form fully between the lower chambers of the heart.

Normally the right side of the heart pumps blood to the lungs to get oxygen, the left side pumps the oxygen-rich blood to the rest of the body. A VSD allows oxygenated blood to mix with deoxygenated blood causing the heart to work harder to provide enough oxygen to the body’s tissues.

VSDs may be of various sizes and they can be present in several locations in the wall between the ventricles. There may be one or more VSD.

It is also possible to acquire a VSD later in life usually after a heart attack or as a complication following certain heart procedures.

Risk factors

Ventricular septal defects may run in families and sometimes may occur with other genetic problems such as Down’s syndrome.

Complications

A small ventricular septal defect may never cause any problem. Medium or large defects can cause a range of disabilities— from mild to life-threatening. Treatment can prevent many complications.

- Heart failure: In a heart with a medium or large VSD, the heart needs to work harder to pump enough blood to the body. Because of this, heart failure can develop if these VSDs are not treated.

- Pulmonary hypertension: Increased blood flow to the lungs due to the VSD causes high blood pressure in the lung arteries which can permanently damage them. This complication can cause a reversal of blood flow through the hole and is known as Eisenmenger syndrome.

- Endocarditis: This heart infection is an uncommon complication.

- Other heart problems: These include abnormal heart rhythms and valve problems.

Prevention

In most cases, one cannot do anything to prevent having a baby with a ventricular septal defect. However, it is important to do everything possible to have a healthy pregnancy.

- Get early prenatal care, even before getting pregnant: Talk to a doctor about the health and discuss any lifestyle changes that he/she may recommend for a healthy pregnancy, before getting pregnant. Also, be sure about any medications one is taking.

- Eat a balanced diet: Include a vitamin supplement that contains folic acid and curb caffeine intake.

- Exercise regularly: Talk with the doctor to develop an exercise plan.

- Avoid consumption of substances that are known risk factors: These include harmful substances such as alcohol, tobacco and banned drugs.

- Avoid infections: Be sure one is up-to-date on all vaccinations before becoming pregnant. Certain types of infections can be harmful to a developing foetus.

- Keep diabetes under control: If one has diabetes, work with the doctor to be sure it is well-controlled before getting pregnant.

Diagnosis

Venticular septal defects often cause a heart murmur that the doctor can hear using a stethoscope. If the doctor hears a heart murmur or finds other signs or symptoms of a heart defect, cardiologist may refer several tests including:

- Echocardiogram: In this test, sound waves produce a video image of the heart. Doctors may use this test to diagnose a ventricular septal defect and determine its size, location and severity. It may also be used to see if there are any other heart problems. Echocardiography can be used on a foetus (foetal echocardiography).

- Electrocardiogram (ECG): This test records the electrical activity of the heart through electrodes attached to the skin and helps diagnose heart defects or rhythm problems.

- Chest X-ray: An X-ray image helps the doctor view the heart and lungs. This can help doctors see if the heart is enlarged and if the lungs have extra fluid.

- Cardiac catheterisation: In this test, a thin, flexible tube is inserted into a blood vessel at the groin or arm and guided through the blood vessels into the heart. Through cardiac catheterisation, doctors can diagnose congenital heart defects and determine the function of the heart valves and chambers.

- Pulse oximetry: A small clip on the fingertip measures the amount of oxygen in the blood.

Treatment

Small VSDs may not cause symptoms and not need treatment. In some cases, they may also close on their own as your child grows. Larger VSDs may need treatment or surgery.

- Catheterization: Closing a ventricular septal defect during catheterisation does not require opening the chest. Rather the doctor inserts a thin tube into a blood vessel in the groin and guides it to the heart. The doctor then uses a specially sized mesh device to close the hole.

- Surgical repair: This procedure usually involves open-heart surgery under general anaesthesia. The surgery requires a heart-lung machine and an incision in the chest. The doctor uses a patch or stitches to close the hole.

- Hybrid procedure: A hybrid procedure uses surgical and catheter-based techniques. Access to the heart is usually through a small incision, and the procedure may be performed without stopping the heart and using the heart-lung machine. A device closes the ventricular septal defect via a catheter placed through the incision.

Follow-up Care

Medical Follow-up

A cardiologist should examine the patient regularly. If the patient’s ventricular septal defect is small or was closed as a child and no other problems are detected, visit annually if possible.

What will the patient need in the future?

Medications may be required only if the patient has heart failure (which is very uncommon) or if the patient has pulmonary hypertension. The cardiologist can monitor the patient with non-invasive tests if needed. These include electrocardiograms, exercise stress tests and echocardiograms.

Activity Restrictions

Most patients won’t need to limit their activity. However, if a patient has pulmonary hypertension, a cardiologist should be consulted in order to manage the patient’s activity.

Prevention of Endocarditis

Unrepaired ventricular septal defect don’t require endocarditis prophylaxis, according to the most recent treatment recommendations. After the VSD is successfully closed, preventive treatment is needed only for a six-month healing period.

Pregnancy

Once the ventricular septal defect is closed and there’s no leftover pulmonary hypertension, the risk from pregnancy is low. If the ventricular septal defect stays open, it will be necessary to talk to the cardiologist.

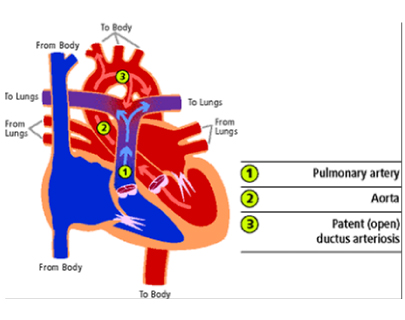

Overview

Patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) is an opening that constantly remains present between the two major blood vessels leading from the heart. This opening called the ductus arteriosus is a normal part of a baby’s circulatory system present before birth but usually closes shortly by itself after birth. If it remains open, it is called a patent ductus arteriosus (PDA).

A small PDA often does not cause problems and might never need treatment. However, a large PDA, if left untreated, can allow poorly oxygenated blood to flow in the wrong direction, weakening the heart muscle and causing heart failure and other complications.

Symptoms

PDA symptoms differ with the size of the defect and whether the newborn baby is born after full-term or is premature. A small PDA might cause no signs or symptoms and go undetected for some time – even until adulthood. A large PDA can cause signs of heart failure soon after birth.

A doctor might first suspect a heart defect during a regular check-up after hearing a heart murmur while listening to the baby’s heart through a stethoscope.

Causes

Congenital heart defects develop from early problems in the heart’s development, but often, there’s no clear cause. Genetic factors might play a role.

Before birth, a vascular connection between two major blood vessels leading from the heart — the aorta and pulmonary artery — is necessary for the baby’s blood circulation. The ductus arteriosus diverts blood from the foetus’s lungs while they develop and the foetus receives oxygen from the mother’s circulation.

After birth, the ductus arteriosus normally closes within two or three days. In premature babies, the connection often takes longer to close. If the connection remains open it’s referred to as a PDA. The abnormal opening causes too much blood to circulate to the child’s lungs and heart. Untreated, the blood pressure in the child’s lungs might increase and the child’s heart might enlarge and weaken.

Risk factors

Risk factors for having a patent ductus arteriosus include:

- Premature birth: PDA occurs more commonly in babies who are born too early than in babies who are born full-term.

- Family history and other genetic conditions: A family history of heart defects and other genetic conditions such as Down’s syndrome increase the risk of having a PDA.

- Rubella infection during pregnancy: If a mother contracts German measles during pregnancy, the baby’s risk of heart defects increases. The Rubella virus crosses the placenta and spreads through the foetus’s circulatory system, damaging blood vessels and organs including the heart.

- Being born at a high altitude: Babies born above 10,000 feet (3,048 meters) have a greater risk of a PDA than babies born at lower altitudes.

- Being female: PDA is twice as common in girls.

Patent Ductus Arteriosus and pregnancy

Most women who have a small PDA can tolerate pregnancy without problems. However, having a larger defect or complications such as heart failure, arrhythmias or pulmonary hypertension can increase the risk of complications during pregnancy. If one has Eisenmenger syndrome, pregnancy should be avoided as it can be life-threatening.

If one has a heart defect, repaired or not should be discussed with a doctor before family planning. In some cases, preconception consultations with doctors who specialise in congenital cardiology, genetics and high-risk obstetric care are needed. Some heart medications can cause serious problems for a developing baby and it might be necessary to stop or adjust the medications before one becomes pregnant.

Prevention

There is no sure way to prevent having a baby with a PDA. However, it is important to do everything possible to have a healthy pregnancy. Here are some of the basics:

- Seek early prenatal care, even before one is pregnant

- Quitting smoking, reducing stress, stopping birth control and so on are things to discuss with the doctor before getting pregnant.

- Also, inform the doctor about any current medication.

- If the mother has a family history of heart defects or other genetic disorders, she should consider talking with a genetic counsellor before becoming pregnant.

- Eat a healthy diet: Include a vitamin supplement that contains folic acid.

- Exercise regularly: Work with the doctor to develop an exercise plan that is right for herself.

- Avoid risks: These include consumption of harmful substances such as alcohol, cigarettes and illegal drugs. Also, avoid hot tubs and saunas.

- Avoid infections: Update vaccinations before becoming pregnant. Certain types of infections can be harmful to a developing baby.

- Keep diabetes under control. If she has diabetes, work with the doctor to manage the condition before and during pregnancy.

Diagnosis

The doctor might suspect that a baby has a PDA based on his/her heartbeat. PDA can cause a heart murmur that the doctor can hear through a stethoscope.

If the doctor suspects a heart defect, he or she might request one or more of the following tests:

- Echocardiogram: Sound waves produce images of the heart that can help the doctor identify a PDA to see if the heart chambers are enlarged and judge how well the heart is pumping. This test also helps the doctor evaluate the heart valves and detect other potential heart defects.

- Chest X-ray: An X-ray image helps the doctor see the condition of the baby’s heart and lungs. An X-ray might reveal conditions other than a heart defect, as well.

- Electrocardiogram/ECG: This test records the electrical activity of the heart that can help the doctor diagnose heart defects or rhythm problems.

- Cardiac catheterisation: This test is not usually necessary for diagnosing a PDA alone but it might be done to examine other congenital heart defects found during an echocardiogram or if a catheter procedure is being considered to treat a PDA. A catheter is a thin, flexible tube that is inserted into a blood vessel at the baby’s groin or arm and guided through it into the heart. Through catheterisation, the doctor may be able to do procedures to close the PDA.

Treatment

Treatments for PDA depend on the age of the person being treated. Options might include:

- Watchful waiting: In a premature baby, a PDA often closes on its own. The doctor will monitor the baby’s heart to make sure the open blood vessel is closing properly. For full-term babies, children and adults who have small PDAs that are not causing other health problems, monitoring might be all that is needed.

- Medications: In a premature baby, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen or indomethacin might be used to help close a PDA. NSAIDs block the hormone-like chemicals in the body that keep the PDA open. NSAIDs cannot close a PDA in full-term babies, children or adults.

- Surgical closure: If medications are not effective and the baby’s condition is severe or causing complications, surgery might be recommended. A surgeon makes a small cut between the baby’s ribs to reach the baby’s heart and repair the open duct using stitches or clips.

- After Surgery: After the surgery, the baby will remain in the hospital for several days for observation. It usually takes a few weeks for a baby to fully recover from a heart surgery. Occasionally, surgical closure might also be recommended for adults who have a PDA that is causing health problems. Possible risks of the surgery include hoarseness, bleeding, infection and a paralysed diaphragm.

- Catheter procedures: Prematurely born baby are too small for catheter procedures. However, if the child does not have PDA-related health problems, the doctor might recommend waiting until the baby is older to do a catheter procedure to correct the PDA. Catheter procedures can also be used to treat children born at full-term, young children and adults. In a catheter procedure, a thin tube is inserted into a blood vessel in the groin and threaded up to the heart. Through the catheter, a plug or coil is inserted to close the ductus arteriosus.

Follow-up Care

If a patient has PDA, even if he/she had surgery as a child, he/she may be at risk of developing complications as an adult. So it’s important to have lifelong follow-up care, especially if he/she had corrective heart surgery. This follow-up care could be as simple as having periodic checkups with the doctor, or it may involve regular testing for complications. The important thing is to discuss the patient’s care plan with his/her doctor and make sure he/she follows all of the doctor’s recommendations. Ideally, a cardiologist trained in treating adults with congenital heart defects will manage such patient’s care.

Lifestyle and home remedies (For Caregivers)

If any baby has a congenital heart defect or has had surgery to correct one, a caregiver might have some concerns about after care. Here are some issues one might be thinking about as a caregiver:

- Preventing infection: For most people who have a PDA, regularly brushing and flossing teeth and regular dental checkups are the best ways to help prevent infection.

- Exercising and play: Caregivers of baby who have congenital heart defects often worry about the risks of forceful activity and rough play, even after successful treatment. Although some children and adults might need to limit the amount or type of exercise, most people who have PDA will lead normal lives. Caregiver’s or the baby’s doctor can advise them about which activities are safe.

Recommendations for a healthy heart for PDA patients and their caregivers

- Eat a balanced diet

- Maintain a proper body weight

- Get the cholesterol levels checked regularly, especially in case of a family history of heart disease

- Avoid smoking or consuming banned drugs

- Get regular medical care from the primary care practitioner

- Keep the follow-up appointments of the patient with the doctors

- Take the medicines as prescribed

- Make sure that the patient has the necessary tests done when the doctor orders them

- Talk with the doctor if the patient/caregiver feels that a treatment or follow-up is making the patient feel worse or is unnecessary. Don’t make any changes to the patient’s plan without consulting the doctor.

- Check on possible side effects of over-the-counter medications, vitamins, herbal preparations or prescription medications before the patient takes them. Discuss any potential cardiac side effects or drug interactions with the primary care physician, cardiologist or pharmacist.

- Discuss the patient’s heart disease with the doctors before having a surgical procedure. Sometimes the surgery or anesthesia can affect the heart.